Summary

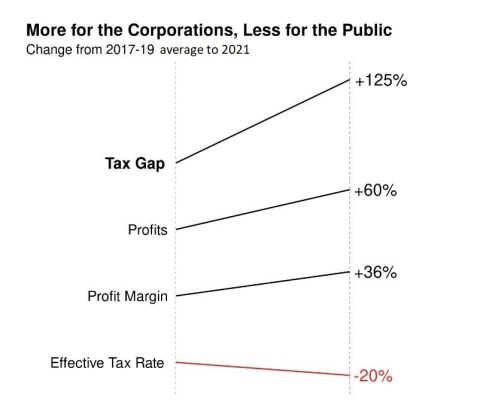

Canada’s biggest corporations are making record high profits and paying income tax at record low rates. This potent combination deprived the public of more than $30 billion in tax revenue in 2021. [1] The foregone revenue could have reduced the 2021 federal and provincial deficit by 20%. [2] Unfortunately, a lack of corporate financial transparency makes it difficult to identify how corporations were able to avoid so much tax. The government needs to explain how corporations are able to avoid such large amounts of tax and take action to reduce the corporate “tax gap”.

The “tax gap” is the difference between how much a taxpayer actually pays in tax, and how much they would pay at the statutory tax rate—the rate stipulated in the tax code. The corporate tax gap grows if corporate profits increase or if the effective tax rate—how much income tax companies actually pay as a share of profits—falls.

Key findings:

- The 2021 effective tax rate for 123 of Canada’s biggest corporations fell to 15% from an average of 19% for 2017 to 2019. At the same time, the pre-tax profits of these companies skyrocketed by 60%.

- The combined federal and provincial statutory tax rate on corporate profits has been around 26.5% since 2012. [3] The difference in 2021 between the statutory rate and the effective rate is the largest since the 2008/9 Global Financial Crisis.

- Lower tax rates, applied to record profits, more than doubled the 2021 tax gap for these 123 corporations to $30 billion from an average of $13.5 billion in 2017 to 2019.

- Relative to GDP, the corporate tax gap jumped to 1.2% from an average of 0.6% from 2017 to 2019.

Report

Corporate tax avoidance is not a new problem. Rather, the enormous increase in the corporate tax gap for 2021 suggests that a persistent problem may be growing worse.

Corporate tax avoidance has significant consequences for government finances and the Canadian economy. It also undermines people’s confidence in our tax system. Above all else, Canadians expect the tax system to be fair. Whether corporations are using questionable tax planning to avoid taxes or simply taking advantage of lucrative loopholes offered by governments, we deserve to know why the corporate tax gap reached such enormous proportions in 2021.

The Tax Gap

In order to calculate the corporate tax gap for 2017 to 2021, we examined the sales, pre-tax profits, and taxes paid for 123 of Canada’s largest corporations. The combined annual tax gap for these companies can be seen in Figure 1.

Note: The annual tax gap is the combined gap between what the 123 companies analyzed actually paid and how much they would have paid at the statutory tax rate.

The tax gap in 2021 was $30 billion. The tax gap in the three years before the pandemic was $13.5 billion. In other words, the 2021 tax gap was more than twice as large.

The enormous increase in the tax gap for 2021 is the product of much higher corporate profits and a lower effective tax rate. Corporate profits increased by 60% over the three years before the pandemic. This was partially due to higher revenues, which increased by 17%, but largely due to higher profit margins, which rose from an average of 12.8% to 17.4%. At the same time, the effective tax rate dropped from an average of 19% to 15.3%.

Note: The effective tax rate is taxes paid as a percentage of pre-tax income. The profit margin is pre-tax income as a share of total revenue.

In other words, although corporate operating costs increased in 2021, those costs were more than passed along to buyers. Canadian corporations were not just responding to inflation. They were helping to drive inflation. And by pushing down their tax rates, the corporations were able to keep more of those inflated profits. The affordability crisis of Canadians and record corporate profits are two sides of the same coin. A windfall profits tax should be considered as a way to address both.

The Largest Tax Gaps

The largest tax gap for 2017 to 2021 belonged to Brookfield Asset Management. Close behind was the oil and gas company Canadian Natural Resources. However, large tax gaps are not limited to just one or two industries. Figure 3 shows the 20 biggest total tax gaps over the last five years. It includes companies from a range of industries. Four of the Big 5 Banks are there (RBC had the 26th largest tax gap). In addition to Canadian Natural Resources, Imperial Oil and Barrick Gold represent extractive companies. Canada’s pipeline giants, Enbridge and TC Energy, are third and sixth, respectively. While Bell was the only telecom to make the Top 20, Rogers is 29th and Telus is 31st.

Note: The tax gap is each company’s total over the years analyzed. Note that Barrick Gold had a slightly negative tax gap in 2021—the company’s effective tax rate was higher than the statutory rate.

How do corporations avoid taxes?

Corporations are able to avoid taxes through a variety of means that range from perfectly legal deductions to tax planning maneuvers of questionable legality.

Among the most significant ways that corporations avoid taxes is by taking advantage of tax havens. Complex and opaque corporate structures allow companies to record revenue and profit in low-tax jurisdictions even if it was not generated in that jurisdiction.

A lack of transparency means we are unable to identify how much corporate tax avoidance is due to profit-shifting as opposed to legitimate business operations in low-tax jurisdictions. In fact, despite examining several years of financial disclosures for some of the companies with the largest tax gaps, we were unable to clarify how they managed to push their tax rates so low.

Although legal, many of the loopholes that the government provides to corporations are of questionable benefit. For example, the business meals and entertainment deduction subsidizes luxury perks enjoyed by corporate executives. [4] Also, unlike the United States, Canada does not limit the amount of executive compensation that companies can claim as a business expense, which exacerbates the large and growing divide between executive and worker pay. [5] Many deductions—such as the ability to carry losses into subsequent years —are intended to reduce investor risks. However, this does not eliminate the risk, it merely socializes it. That means investors who get to direct investment get to claim the profits from successful investments, and foist a portion of the losses onto the public through reduced tax revenue.

There are incentives for corporations to push at the boundaries of tax laws. The CRA continues to be under-funded and investigating corporate taxes is extremely complex. It takes significant time and resources to identify questionable transactions, and even more time and effort to challenge those transactions. Yet, the penalties for contravening the law are meagre.

For example, one of the tools the government has to stop aggressive tax avoidance is the ‘General Anti-avoidance Rule’, known as GAAR. This is intended to stop corporations from using tax plans that might adhere to the letter of the law, but violate the purpose of the law, such as organizing a transaction solely to take advantage of some tax benefit. However, as it is currently legislated, there is no penalty associated with GAAR violations. That means even if a corporation loses a claimed deduction, the cost is only the tax they would have paid in the first place.

Although Justin Trudeau’s government has acknowledged the problem of excessive corporate power and tax avoidance, it has done too little to confront it. It is finally undertaking a long overdue update of GAAR, but has delayed consultations on the use of GAAR and exploitation of tax havens. This is indicative of an overall lack of urgency.

The Good News, Maybe

Although the enormous increase in the tax gap in 2021 is very troublesome, we should not assume worsening corporate tax avoidance is inevitable.

Our analysis is an update of research published in 2017 by the Toronto Star and Corporate Knights, which looked at the corporate tax gap for 2011 to 2016. [6] In 2016 the effective tax rate dropped to 15.5%. We found that the following three years all had markedly higher rates.

Potentially positive developments are more apparent when we examine individual companies. Although, as described above, the Big 5 Banks have some of the largest tax gaps for 2017 to 2021, their effective tax rates have generally been higher. In 2017 to 2019, all of the Big 5 Banks had effective tax rates at least four points higher than during the previous six years. In 2021, the picture is more mixed. CIBC had an effective tax rate below its 2011 to 2016 average, while the Bank of Montreal’s rate was even higher than its average for 2017 to 2019.

This variability among corporations in the same business raises red flags about the methods used to avoid taxes. How is one bank able to significantly cut their tax payments while another is not?

Unfortunately, just as we are unable to determine why the corporate tax gap has grown so substantially, we are unable to determine why effective tax rates have risen for some companies. Is the credit due to government actions? If so, which actions and what lessons are being learned?

Conclusion

Canada’s largest corporations are powerful forces in our economy. Their combined revenue is more than twice the GDP of Western Canada. Enormous power must be balanced with high levels of transparency and accountability. The government needs to investigate and explain why the 2021 corporate tax gap was so much larger than earlier years. We cannot effectively tackle the tax gap if it isn’t clear how companies are lowering their taxes.

Canadians deserve greater public transparency of corporate financial data. The government has taken commendable steps to improve transparency with plans for a beneficial ownership registry. But if we are going to allow corporations to control so much of our economy, then they need to be more accountable. Canadians deserve to know how corporations are avoiding taxes so they can decide if it is legitimate and beneficial or not.

Along with greater transparency, there are steps the government can take to reduce the tax gap. These are some of the actions that should be taken:

- Raise the corporate income tax rate: Low corporate taxes are a failed experiment that needs to end. The federal corporate income tax rate should be raised to 20% from 15%.

- Implement a minimum tax on book profits, similar to the one in the United States’ recently passed Inflation Reduction Act: This acts as a check on corporate exploitation of tax loopholes by taxing the profits that corporations tout to their shareholders. If Canada had imposed a 15% minimum tax on the 2021 book profits of the 123 companies analyzed, it would have brought in $11 billion in revenue.

- Close the capital gains loophole: Only half of capital gains are subject to income tax. This costs the government about $22 billion a year in lost revenue. More than half of that lost revenue enriches corporations.

- Additional measures the government could take to rein in the tax gap include: introduce a windfall profits tax, restrict executive salary deductions, reform business meals and entertainment deductions, lower the limit on interest deductibility, implement a tax on digital services.

Of course, defenders of corporate interests will claim that higher corporate taxes lead to lower investment or higher prices. This mantra has been repeatedly debunked. Decades of low corporate taxes have not produced the promised investment and jobs. [7] In reality, corporations are raising prices despite ultra-low taxes, making life less affordable for Canadians. We all stand to benefit from greater corporate transparency and fairer taxation.

Endnotes

- All figures in Canadian dollars. Our analysis was restricted to 123 publicly-listed, Canadian-headquartered corporations with a market capitalization of $2 billion or more at the end of 2021. Firms included in the analysis 1) had data covering at least 2017 to 2021, and 2) positive total pre-tax profits for 2017 to 2021. Our analysis excluded real estate investment trusts because of their different tax treatment.

- Federal and provincial deficit values come from StatCan table 36-10-0118-01.

- Data on statutory tax rates comes from Finances of the Nation (https://financesofthenation.ca/statutory-tax-rates/).

- https://www.taxfairness.ca/en/resources/explainers/explainer-what-busin…

- https://policyalternatives.ca/BoundlessBonuses

- We replicated the method used in the Toronto Star / Corporate Knights analysis. The two analyses are not strictly comparable because the corporations analyzed are slightly different because we updated the set of corporations based on 2021 market capitalization. However, because big companies tend to remain big there is significant overlap between the set of corporations examined.

- David Hope and Julian Limberg. 2022. “The economic consequences of major tax cuts for the rich”, Socio-Economic Review, 20(2): 539-59.